|

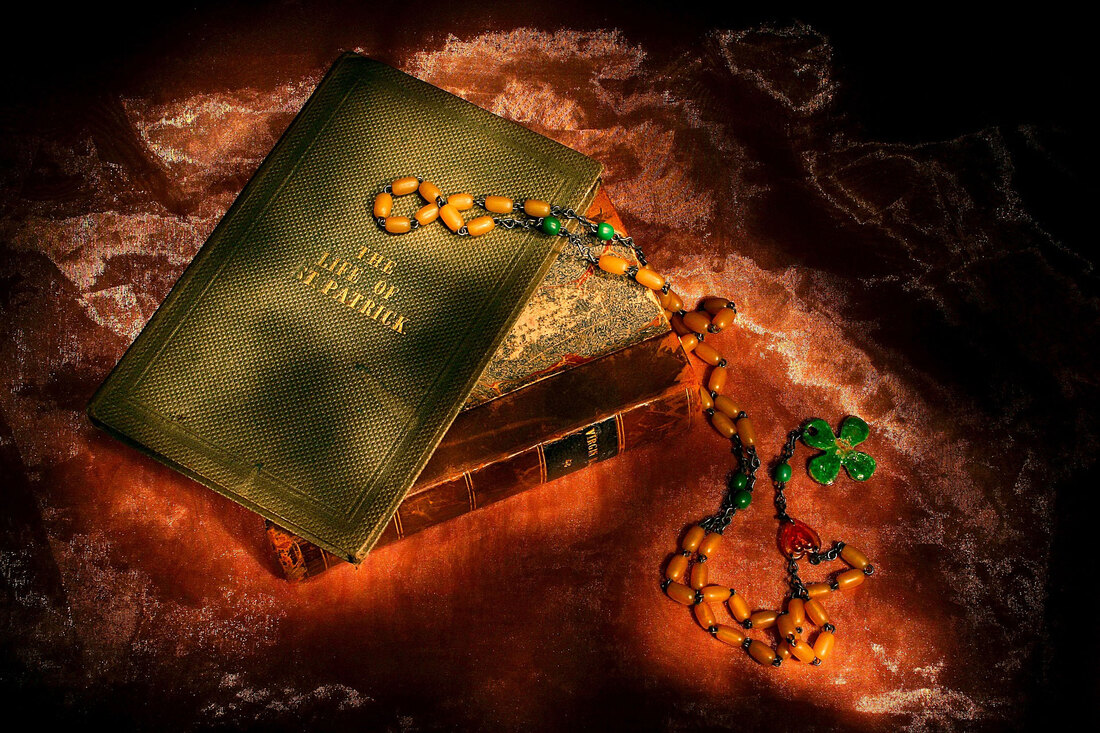

The legend of the shamrock is closely tied to St. Patrick—a man who was born in Roman Britain, lived as a slave in Ireland as a youth, escaped his bondage, and then spent some time back in England, where he seems to have become a Christian missionary or priest. St. Patrick—described by Irish Central as landing back in Ireland sometime around 431 AD—used the shamrock (the three-leaf clover) to teach the native Celtic peoples about the Holy Trinity (Catholics will know this as the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost). St. Patrick later became the patron saint of Ireland, and the shamrock became an emblem of the Irish and Ireland and a symbol of good luck. Whether or not this legend is a true story is up for debate, but Irish “history” and myth often meld together, blurring the distinction between the two. The story of the shamrock doesn’t seem to have been widely recorded until the 1600s. St. Patrick was never formally canonized by the Roman Catholic Church, further complicating the story. But we celebrate his feast day on the day of his death, March 17th. Do not confuse the four-leaf clover with the shamrock! I have childhood memories of lying in the grass, combing through clover patches, looking for the rare four-leaf clover. And I did manage to find a couple! The three-leaf variety was sadly overlooked. Back then, I didn't appreciate the deeper meaning. The traditional shamrock—seamrog in Irish Gaelic—is the three-leaf version. This may have to do with the fact that the number three has had special relevance in ancient Ireland and was important to the Celts, who were the native people of Ireland. According to Irish Around the World, the goddess Anu had a close association with the shamrock, with the three petals symbolizing the three stages of a woman—the maiden, the mother, and the crone. This is just one example of the strong association with the number three with sacred beliefs. According to an article on shamrockgift.com (which takes a deep dive into this subject), during the 1500s and 1600s, the English used the shamrock as a derogatory way to symbolize the Irish, citing shamrocks as a popular food for which the Irish were said to forage. Even before the famines of the 1800s and the troubled relationship between the English and Irish during the twentieth century, the English regarded the Irish as backward, wild, and savage—uncivilized, one might say. And the shamrock became associated with them. In the coming centuries, the Irish took that negative connotation and made it their own by using it as emblems for various resistance groups. It came to symbolize the Irish fight against their oppressors and eventually became the national flower, if you will, of Ireland and the Irish people. It showed up in poetry and music, art and symbols. Its popularity in art and culture continues to grow. As the Irish emigrated to other countries in recent centuries, their beloved shamrock and collective memory of St. Patrick traveled with them. In their native land, the shamrock was formally recognized as the national flower of Ireland and trademarked in the 1980s (according to Irish Around the World). Along with the national symbol of the harp, the shamrock can be found on flags and art globally. And finally, the proper abbreviation for St. Patrick’s Day is St. Paddy’s Day…NOT St. Patty’s Day. Patrick in the Irish language is Padraig, hence the shortened version, Paddy. (Just a little tidbit of information for those who care!) So Happy St. Paddy’s Day! Erin go Bragh!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Author

Some of the posts on this site contain affiliate links. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. Categories

All

Archives

October 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed